General Revelation, Universalism in Miniature

and Truncated Galatianism:

Their Interconnectedness

by K. Neill Foster, Ph. D.

Evangelical Theological Society

November 1997

The debate among evangelicals about inclusivism and the salvation that is alone in Jesus Christ has been widely considered and there are a number of fine discussions available. My intent is to briefly show the interconnectedness of General Revelation, Universalism and Galatianism and their relationships to each other.

Since the material is like a seamless robe, intricately woven together, I will not attempt an outline. What I do provide is three definitions as we move through the material.

Further, in delimitation since space and time forbid, I decline to enter into the theological rationales offered by the various expressions of error. My express intent is to show connectedness and interrelationships between Universalism, Inclusivism and Galatianism.

GENERAL REVELATION

There are at least three kinds of revelation of divine things given by God. There is to begin with, the written revelation of God which we call the Bible. "All scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work" (2 Timothy 3:16-17).

Secondly, Jesus Christ was born of the virgin Mary, lived a sinless life, was crucified by Pontius Pilate, died and rose again after three days, ascended into heaven and is now seated at the right hand of the Father. He was and is the Word of God incarnate. "The word became flesh and lived for a while among us" (John 1:14). He was in person, in the flesh, Revelation incarnate.

Third, general revelation is also a biblical idea. The heavens declare God's handiwork. The New International Version translates further as follows:

The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour forth speech;

night after night they display knowledge.

There is no speech or language

where their voice is not heard.

Their voice goes out into all the earth,

their words to the end of the world (Psalm 19:1-4).

One of the metaphors for general revelation suggests that God has dressed Himself in nature and can be seen as "visible apparel." Luther suggests that those who strive to reach God without these veils and coverings are attempting to scale heaven without a ladder (Parker, 1947: 1-33, 34).

General Revelation includes divine self-disclosure in the natural order and in man, that is, external general revelation and internal general revelation. Taken into account are the complexity and design of the cosmos (Psalm 19, Romans 1); the continuing work of providence (Acts 14:17; 17:26-29); the imprinted awareness and perception of man regarding God's law (Romans 2), the yearning for eternity with the spirit/soul component returning to God (Ecclesiastes 3:11, 12:7), and God's existence, character and requirement of thankfulness, glory, service and worship (Romans 1). At best general revelation serves the following purposes: Discloses to men their accountability to the God who made them, prepares them for the coming of the gospel of Jesus Christ as God's only remedy, and enables them to think God's thoughts after Him and thus exercise an appropriate stewardship over the creation as God originally commanded Him (Genesis 1:28; Psalm 8:6). (Cuccaro, 1997:1)

Calvin for his part was emphatic that natural revelation could not save. "The whole tenor of Calvin's theology is [that man is] suffering not from dimness of sight but from total incurable blindness" (Parker, 1947:1-37).

Definition # 1

Natural revelation is this world in its fullest meaning and the universe around it expressing themselves as orderly, intricate, clearly made by a Creator who wishes to be known.

Natural Revelation, A Saving Voice?

How much does natural revelation say? Does it have a saving voice? Paul makes clear that humanity is without excuse, admitting that natural revelation has a message that is clear, sufficiently specific to condemn but not to save. "For since the creation of the world God's invisible qualities - his eternal power and divine nature - have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that men are without excuse" (Romans 1:20) There is no hint that this knowledge of God that comes from His creation has any other function than to witness to His power and nature. But that very message

supports the expectation of special revelation. General revelation also teaches us how and where to look for a revelation from God that addresses concrete human needs, so that the divine remedy can be recognized and appropriated by human persons (R. Douglas Geivett and W. Gary Phillips 1995:218).

An Unintended Arena

Don Richardson's Eternity in Their Hearts appears to have inadvertently opened the door for many more to be saved through general revelation than had been generally thought (Covell 1993:164). Indeed, the inclusivist challenge to orthodoxy in the last ten years has been focused here. Can general revelation be made to be a saving instrument? Richardson is not an inclusivist, but his ideas have been captured for release in an unintended arena.

Lausanne

The Lausanne Covenant is very clear that God has revealed Himself in a general way in nature and that this revelation is not salvific and only results in people rejecting the truth (Covell 1993:164). Nevertheless, since Lausanne,

a small number of evangelical writers affirm that divine self-revelation (the illumination of the divine Logos plus the testimony of God's Creation) is at least potentially salvific, . . . This general revelation is broad enough, they claim, to include a sense of God's kindness and mercy, as well as his claims on the human conscience. If the individual responds to this sense of need and gives oneself in "self-abandonment to God's mercy," then salvation is possible (Covell 1993:164)

Salvation through general revelation is not a new idea. What is new is the evangelical suggestion that just a few will be saved in this manner.

UNIVERSALISM

But we should not delude ourselves, universalism is back. It is in a new form and the terms are new. The ancient heresy has returned. Right now it is no longer the swaggering giant of the past, with whom all the world would be saved, no matter what.

This new evangelical version walks with baby steps and lisps with tiny voice. Only a very few now will be saved without ever once hearing of Jesus Christ.

Definition #2

Universalistic inclusivism, universalism in miniature, postulates that a few holy pagans will receive illumination through general revelation which will be adequate enough in itself to awaken saving faith in Jesus Christ.

Trevor Hart correctly emphasizes that we should be thinking in terms of "universalisms [plural], rather than [just] universalism" (Hart 1992:3). Christy Wilson, Professor emeritus of World Evangelism at Gordon-Conwell Seminary is emphatic on the subject of inclusivism and implicit Christianity.

The danger of inclusivism and pluralism is that they end up as universalism. This can be seen by the initial forms of universalism in the writings of various authors. . . . Christy Wilson, Jr., 1992:11).

The universalism advocated in the nineteenth century has been replaced with what can best be described as a nuanced universalism. Like a virus which spins off a more deadly strain, it is more subtle, more deceptive and probably more dangerous to modem evangelicals presently awash in a sea of pluralism and relativism.

This new universalism assures us that Melchezidec did not receive a revelation from God, he was a "holy pagan," just as in the New Testament, Cornelius was likewise a "pagan saint," even though Peter specifically went to him with the words of salvation (Acts 11:14). This new universalism is in fact quite resistant to the idea that just as God revealed Himself to Abraham He might reveal Himself to others. It prefers to walk some holy pagans into the kingdom without any conscious knowledge at all about Jesus Christ, making Him somewhat unnecessary, thus eroding somewhat all that He is in the process.

Likewise this universalism in miniature rests confidently on natural revelation as a saving instrument. The lost obviously know that Someone has made this world. Salvation through natural revelation is a pillar in this new variety of ancient error even though Romans 1-3 repudiates it.

Negating the Old Missionary Compulsion

The new universalism reacts with disdain to the lostness of mankind. Often called inclusivism, it assures us that some who never hear will nevertheless be saved, setting itself against the plain statements of Scripture (Romans 10:13-15) while at the same time cutting the nerve of missionary endeavor. As John Hick, the pluralist, makes clear, inclusivism [this new form of universalism] will certainly "negate the old missionary compulsion" (Hick 1993:143).

Like universalism in full form, this miniature version profoundly dislikes hell and eternal punishment. It wants to find an alternate route into the kingdom for at least some.

GALATIANISM

One last observation, though obviously a very important one - this new universalism finally arrives at salvation by works. Forgetting that Paul clearly states that we are saved by faith, "not of works lest any man should boast" (Ephesians 2:8-9), the holy pagans are identified, finally, by their works. It finds the Galatianism of the first century a natural ally in its deadly war against orthodoxy and biblical truth.

In Acts 15 and in Galatians the violation to the gospel amounts to adding the keeping of the law to faith in Christ as the way to salvation. This is an amalgam, a hybrid, of salvation by faith alone (taught by Paul) and legalistic Judaism or the later Pelagianism (pure salvation by works that looks to Christ only as an example of and inspiration to obedience to the whole will of God.) (Cuccaro, 1997:2)

Definition #3

Galatianism is salvation by faith plus works. The new Galatianism is diminutive in quantity and quality. Some, a very very few, will be saved by their blurry faith and godly lifestyles.

The Early Church

Among the church fathers, Origin (230 AD) was known for his affinity for universalism (Norris 1992:47). To this day, Origen is suspect because of the universalistic virus.

As the fifth century dawned, Augustine began a twenty-year argument with Pelagius, the British monk who argued a kind of salvation by works. The new universalism is frequently connected with that heresy called pelagianism. And what really was that error? Pelagius had a rather high estimate of the possibilities of human nature (Chadwick 1986:108), almost exactly the view of the newest variety of universalism. "Salvation by good works," after all, has always been a faithful friend of universalism, providing always a hopeful path for deviant salvation.

The Twentieth Century

The seed for this mini-universalism among evangelicals is probably found in a 1907 comment by Augustus H. Strong. He uses the term "implicit faith."

Since Christ is the Word of God and the Truth of God, he may be received even by those who have not heard of his manifestation in the flesh. A proud and self-righteous morality is inconsistent with saving faith; but a humble and penitent reliance upon God, as a savior from sin and a guide of conduct, is an implicit faith in Christ; [emphasis added] (Strong 1907:842)

Vatican II and Karl Rahner

More than fifty years later, Vatican II (1963) once again popularized universalistic ideas. And Karl Rahner, a Roman Catholic theologian was sharp on the heels of Vatican II with speculative, (and universalistic) writing not about "implicit faith" and "implicit Christians" as wavering Protestants seem to prefer, but about "anonymous" Christians, those who through no fault of their own had never heard the Christian message, but would nevertheless be saved by the godly life style exhibited.

Therefore no matter what a man states in his conceptual, theoretical and religious reflection, anyone who does not say in his heart, "there is no God" (like the "fool" in the psalm) but testifies to him by the radical acceptance of his being, is a believer. But if in this way he believes in deed and truth in the holy mystery of God, if he does not suppress this truth but leaves it free play, then the grace of this truth by which he allows himself to be led is always already the grace of the Father in his Son. And anyone who has let himself be taken hold of by this grace can be called with every right an "anonymous Christian" (Rahner 1969: 6:395).

There is evidence in this initial statement of Rahner's that the backdrop of his commentary is undeniably "salvation by works" Roman Catholicism. We should not forget either that Vatican II had just taken place, declaring itself in universalistic terms.

They also can attain to everlasting salvation who through no fault of their own do not know the gospel of Christ or his church, yet sincerely seek God, and moved by grace, strive by their deeds to do his will as it is known to them through the dictates of conscience [emphasis added] (Vatican II, Dogmatic Constitution of the Church, par. 16).

These anonymous Christians, sometimes also called "holy pagans" are by definition persons who have been awakened by natural revelation. Though they have never once heard of Jesus Christ, they are supposedly to be saved.

Church Growth Emerges

During the twenty-five years after Vatican II, the Church Growth Movement emerged, embracing the social sciences and promising to make them subservient to theology, the queen of the sciences. It never happened (Cook 1996: July I), and anthropology, especially, was quick to offer rationales suggesting that holy pagans with godly lifestyles might indeed be truly saved (Kraft 1979:254-255). Universalism could be and was argued against while a truncated universalism was at the very same time being inadvertently accepted.

A Pivotal Study

Though Strong's error lay dormant for eighty years, it apparently had its effect. In 1987 a study done by James Davison Hunter, a sociologist from the University of Virginia warned that the new generation of evangelical students no longer unanimously believed in the lostness of mankind, but did believe that a godly lifestyle might be sufficient for salvation especially for those who had never heard. He considered this mix of eroded orthodoxy and belief in salvation by works for just a few a new form of universalism. Hunter is particularly insightful as to the instrusion of the salvation by works paradigm which inserts itself into the "salvation by faith alone" mode of thinking prevailing among evangelicals of previous generations. In describing what he calls "sharply modified universalism" (1987:47), Hunter quickly moves to the salvation by works theme in anticipating evangelical beliefs of the emerging generation:

For a substantial minority of the coming generation, there appears to be a middle ground that did not. . . exist for previous generations. For the unevangelized and for those who reveal exceptional Christian virtue but are not professed Christians [emphasis added], there is hope that they also will receive salvation. . . . Needless to say, this posture would, and in fact does lessen substantially the sense of urgency to evangelize the unreached (1987:47).

Hunter clearly saw these eventualities:

. . . only 67 percent [of evangelical collegians and seminarians] agreed that "unless missionaries and others are successful in converting people in non-Christian lands, these people will have no chance for salvation" (Hunter 1987:36).

Also take note, Hunter saw something else coming, and early on caught the essence of salvation by works in the postulation of salvation for special cases among those who have never heard. The "virtuous pagans" who never hear of Jesus Christ but still would be saved are clearly to be "exemplary people whose lives were characterized by extraordinary good will and charity" (1987:37). "There is entailed in this view a faith + works amalgam of some kind" (Cuccaro 1997:2).

Larry Poston in his unpublished paper likewise labels these developments universalistic.

. . . a growing trend exists among traditional, conservative Evangelicals to try to "rescue" God's justice and assuage the guilt associated with salvation of only specifically chosen individuals by positing various forms of universalism and modifications of universalism, including ideas involving "implicit Christians," chances to hear the Gospel after death, and the like.

. . . these trends represent concessions to "the spirit of the age," which. . . is essentially universalist and pluralist in character (Larry Poston 1994:46).

Why the Label?

Why the universalistic label? Universalism is the belief that all will be saved apart from the faith that is in Jesus Christ. Inclusivism, while wanting just a few to be saved apart from the conscious knowledge of Jesus Christ, dips into the same fountain of unbelief.

What does it matter if the billions of earth are to be saved by discounting the sacrifice of Jesus or just a few are to be saved by the discounting the sacrifice of Jesus? The discounting has taken place. Jesus Christ is not necessary if universalism is true; Jesus Christ is not totally necessary if inclusivism is true. Thus, I argue, not alone, that inclusivism deserves a universalistic label. Erickson, Hunter and Poston are correct.

Christological Error

The discounting of Jesus Christ brings us up short. Christy Wilson is emphatic on this point. While he was addressing "implicit" concepts, his commentary is no less apt when applied to the universalistic flavor of inclusivism.

What is this but a form of salvation apart from Christ along with good works? It makes the cross of Christ of no effect and certainly involves Christological error (Christy Wilson 1992:11).

In a chapter addressing universalist Christology, in which incIusivism is a sub-point, Erickson makes himself very clear.

The exclusivism implicit within the orthodox view of Christ as God incarnate presents a problem for a number of twentieth-century theologians. Actually, the issue has been with Christianity virtually from its beginning in the form of universalism. . . . In recent years, however, with the phenomenon of globalization, . . . the problem has become more pronounced. The shrinking world has resulted, for some Christians and theologians, in a shrunken Christ [emphasis added] (Erickson 1991:276).

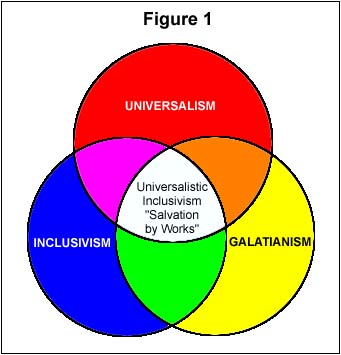

Inclusivism also connects the new universalism to salvation by works. I postulated as we began that it might be shown that the three concepts might be strung together in a connecting chain. While not all will agree with the linkage, the chain clearly exists. See Figure 1.

The Nineteen Nineties

In 1990 John Stott, the scholarly British evangelical openly embraced annihilation, abandoning eternal punishment. Stott opened the flood gates. Books and articles have multiplied on every side.

In this same time period, following Hunter's lead, Millard Erickson also described this belief about implicit faith and implicit Christians as "universalistic" inclusivism (1991:29). To date I have not seen in Erickson any admission of the salvation by works theme within inclusivism.

Most notably, Clark Pinnock and John Sanders followed with books which, interestingly, advocated two things: the salvation of holy pagans in a kind of truncated universalism aided and abetted by, though they both deny it, salvation by works.

Ronald Nash and others were quick to point out that inclusivism as it came to be called-indeed the inclusivism of Pinnock and Sanders was also - inevitably, salvation by works. I find it ironic that Nash who probably has done the most to deflate inclusivism is adamant that inclusivists are not universalists (1994:115). While he is technically correct, he overlooks the universalistic underbelly of inclusivism. At that point he differs with Erickson, Hunter, Poston and others. Still, Nash convincingly repudiates inclusivism and shows its works-orientation.

The old gospel grounds salvation on the work of God while the new gospel makes salvation dependent on the work of man. The old gospel views faith as an integral part of God's gift of salvation while the new gospel sees faith as man's role in salvation (1994:133).

Conclusion

It is correct to refer to inclusivism as a form of universalism. Hunter calls it "sharply modified universalism" (1987:47). Erickson joins the two commonly used ideas, calling the error "universalistic inclusivism" (1991:29).

If, like Erickson, We may "lnarrowly" and "privately" define universalism as the belief that apart from clear belief in Christ and apart from the preaching of the gospel, man may be saved, then this inclusivism is quasi-universalism, it is selective universalism, it is universalism in a mustard seed. Not full-blown universalism, it is lethal, certain to spread and potentially damning to millions. For that reason, we must be vigilant. We stand warned. Even a brief explanation such as this is, like Paul's corrective argumentation centuries ago, could undermine, erode and cut the ground from under false teachers and false teaching (2 Corinthians 11:12). Were that to happen, I would be gratified.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chadwick, Henry.

1966 Early Christian Thought and the Classical Tradition: Studies in Justin, Clement and Origen. Oxford: Publishing House unspecified.

Cook, Arnold L.

1996 Public address, General Assembly of The Christian and Missionary Alliance in Canada, July I, Regina, Saskatchewan.

Cuccaro, Elio.

1997 Private correspondence.

D'Costa, Gavin, editor.

1990 Christian Uniqueness Reconsidered.

MaryknoIl, NY: Orbis Books.

Dixon, Larry.

1992 The Other side of the Good News.

Wheaton, IL: Victor Books.

Erickson, Millard J.

1996 How Shall They Be Saved?

Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

1993 The Evangelical Mind and Heart.

Grand Rapids: Raker Book House.

1991 The Word Became Flesh.

Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

1991 "The State of the Question," Through No Fault of Their Own.

Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

Fernando, Ajith.

1991 Crucial Questions about Hell.

Wheaton, 1L: Crossway Books.

Gnanakan, Ken.

1992 The Pluralistic Predicament.

Bangalore, India: Theological Book Trust.

Hick, John and Paul F. Knitter, Editors.

1987 The Myth of Christian Uniqueness.

MaryknoIl, NY: Orbis Books.

Kraft, Charles.

1979 Christianity in Culture.

Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

McCrossan, T.J.

1941 The Bible: Its Hell and Its Ages.

Seattle, W A: By the author.

Nash, Ronald H.

1994 Is Jesus the Only Savior?

Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Okholm, Dennis L. and Timothy L. Phillips, Editors.

1995 More than One Way?

Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Parker, T .H.L.

1947 "Calvin's Concept of Revelation."

Scottish Journal of Theology, 1:29-41.

Pinnock, Clark H.

1992 A Wideness in God's Mercy.

Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Poston, Larry.

1997 "Biblical Christianity and the World Religions."

Nyack College, Nyack, NY: Unpublished paper.

Richardson, Don.

1981 Eternity in Their Hearts.

Ventura, CA: Regal Books.

Rommen, Edward and Harold Netland, Editors.

1995 Christianity and the Religions.

Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library.

S. Cameron, Nigel M.

1992 Universalism and the Doctrine of Hell.

Grand Rapids: Baker Book House.

Sanders, John.

1992 No Other Name.

Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Company.

Van Engen, Charles, Dean S. Gilliland and Paul Pierson, Editors.

1993 The Good News of the Kingdom.

Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

Wilson, Jr., J. Christy.

1992 Unpublished paper.